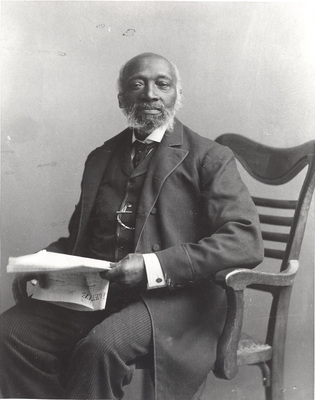

Moses Viney 70 Years with Union

(March 10, 1817 – January 10, 1909)

Born a slave on a plantation in Maryland, the eldest of twenty-one children, Moses Viney worked in the fields until becoming a butler for the plantation owner. In 1840, upon overhearing that he might soon be sold, Viney decided to escape and travel north where he could be free. He and his friends used the Underground Railroad and passed through Philadelphia, New York City, and Troy before Viney ended up in Schenectady. In 1842, Eliphalet Nott, President of Union College, hired him as a servant. Viney served as his coachman and messenger and took care of Nott in his illnesses, giving him massages to soothe the pains of his rheumatism and caring for him after his strokes. He also interacted with the students, including Chester A. Arthur and William Seward’s son Frederick. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, Viney’s life in Schenectady was in danger, especially when he saw his former master in the city. Nott then sent his grandson to Maryland to find out what it would take to purchase Viney’s freedom, but rather than pay the $1,900 demanded, Nott sent Viney to Canada while he continued negotiations. Only after Nott was able to procure Viney’s freedom in 1855 — for the much reduced sum of $120 — did Viney return to Schenectady. He lived with his wife Anna in a small house on the Union College grounds and served Nott until the latter’s death in 1866. Although he received a substantial bequest from Nott’s estate and subsequently moved off campus, he continued to serve Nott’s widow Urania until her own death in 1886.

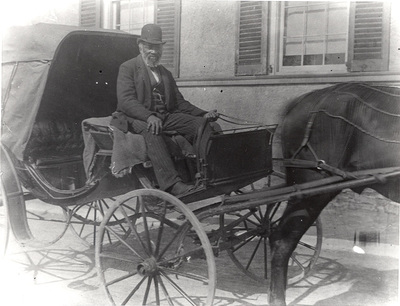

Viney’s wife Anna had died the previous year, and he decided to set up an independent livery service of his own after Urania’s death, purchasing a horse and three-wheeled for the purpose from her estate. Mrs. Perkins often used his carriage service, which Viney continued to operate successfully on campus and in town until his retirement at the age of 84 in 1901. Apparently, one of Mrs. Perkins’ dogs, Flop, particularly enjoyed Viney’s company:

We went downtown today with Moses and did errands… Flop tried to hide again in the carriage and Moses says he lies quite contentedly in the barn (November 6, 1897).

At the time of Mrs. Perkins’ letters, Viney was already a very old man, and constantly being out in the Schenectady weather was probably not beneficial to his health.

I think everybody is a little worn by this unseasonable weather, and poor Moses can hardly stand up. Fortunately he can do a great deal of sitting down. Jack says that Moses and I and Mrs. Peissner will infect the sleigh with rheumatism and everybody else will catch it (March 23, 1896).

During Viney’s nearly seventy-year association with Union, he became something of a living part of Union lore. He was greatly appreciated by many members of the College community; President Nott prized his great integrity, industry, and capability, and Urania Nott cited his intelligence and ambitious temperament. However, despite Viney’s pleasant relations within the College, he was still a black man on an all-white campus with many southern students. He worked for the Notts for just ten dollars a month, and though he was buried in Schenectady’s Vale Cemetery, it was in a segregated section later renamed the Ancestral Plot. Nevertheless, many alumni were delighted when Mrs. Raymond requested that Viney be made a part of Commencement week. He served as the doorman to the president’s reception until a year before his death in 1909.